Translation, an indispensable task for furthering the mission of the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF)

“The translator is not merely changing words from one language to another, but rather is a significant producer.” Their work goes well beyond translating a text. It implies interpreting the meaning and producing a new text with an equal meaning. Translation brings down barriers between languages, making an interconnection between cultures possible, and in this way, a greater rapproachement between the peoples, their values, ideas, customs and traditions.

With the new translation technologies, is the profession of the translator threatened? The answer is ‘no’, because machines can’t feel emotions nor interpret them, at least for now.

The activity is recognized and even has a special date on the international calendar. September 30 is celebrated as International Translation Day, in honor of Saint Jerome, translator of the Bible from ancient Greek and Hebrew to Latin, the official language of the Catholic Church during that period. The date, established by the International Federation of Translators, refers to the day of the death of Saint Jerome, which took place in 419 or 420 AD.

The translator is an essential professional for furthering the work of the Fraternity – International Humanitarian Federation(FIHF), which operates in 28 countries and brings together 24 national and international civil associations through activities of a volunteer, humanitarian, environmental, cultural and philosophic nature.

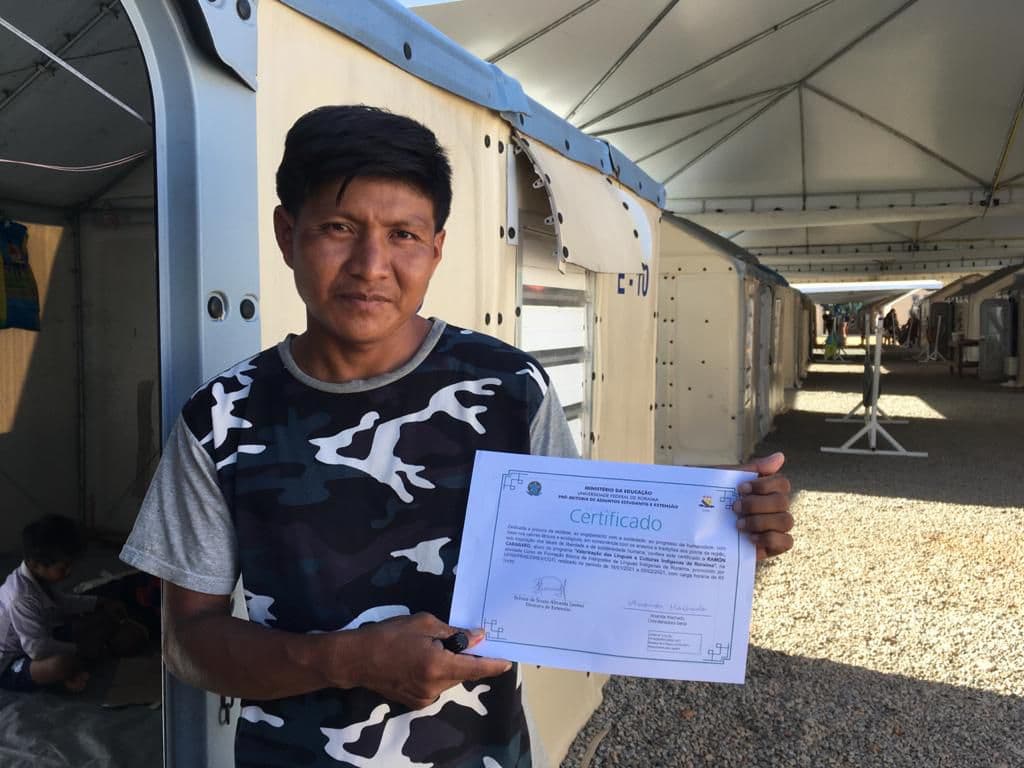

Translators and interpreters of the Warao and E’ñepa ethnicities

In the Roraima Humanitarian Mission, which works with Venezuelan indigenous refugees, the task of the translator makes it possible to understand the verbal and non-verbal language of the assisted peoples – natives of the Warao and E’ñepa tribes among others – on behalf of the members of Operation Welcome, in which the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF) is the implementing partner of the UNHCR, and responsible for the management of five indigenous shelters in Roraima and the Transit Shelter of Manaus (TSM). It also makes it possible for those assisted to understand what is being said to them by the managers and collaborators of the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF).

The indigenous refugee Yurkeline Isseni Marin Ratia, 30 years old, is translator and interpreter of the Warao ethnic group. She speaks about the relevance of her task for her people and comments on her work: “Translation is important because some people don’t understand either Portuguese or Spanish. It is fundamental, because we are outside of our country. What is most important is to translate the same words they said, and that our Warao brother or sister feels happy when we take our language seriously. For me, what is most important is to help our Warao and non-Warao brother and sister. If there is love in our work, there is more responsibility with our community.”

Another indigenous Venezuelan, Ramón Carabaño García, 28 years old, works as a translator for the E’ñepa people. For him, working as a translator makes it possible to understand the language between his sibling E’ñepa and Brazilians. He says: “To translate, we need to write in E’ñepa and understand that word. If we don’t understand it, we translated it wrong.”

His work ranges from accompanying indigenous people of his ethnicity outside of the shelters in procedures such as obtaining documents, going to the hospital, translating medical prescriptions, to being an interpreter in meetings with the administrators of the shelters and others.

He also translates printed publications addressed to his people: “Now we are translating an information brochure that deals with subjects such as numbers, greetings, illnesses, sexual violence.”

“Words and phrases have an energy charge”

The Argentine, Brenda Rosamaría Cutrell, retired professor of spiritual philosophy, resident in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, EE.UU., works as a translator in various publications of the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF). Most of the time, she translates from Spanish to English, and in some cases, from English into Spanish.

Her work began with the translation into English of books by the spiritual teacher, José Trigueirinho Netto, founder of the Figueira Light-Community and co-founder of the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF), at the request of her teacher, Carol Parrish-Harra, a friend of Trigueirinho’s. She recalls: “Although I had never learned Portuguese, when I went to the Figueira Light-Community in 2000, I understood Trigueirinho’s talks perfectly. It was an interesting experience. I have translated various books: The Esoteric Glossary, Oceans can Hear, Noah’s Vessel, Our Life in Dreams, The Path of the Fire, Unveiled Secrets, among others. I also translated his talks, published as CDs with English superimposed on the recordings.”

Nine years ago, Brenda was invited for a special mission, which she carries out as a volunteer: to translate the messages of the Divine Messengers. After that, she became involved with the work of the Humanitarian Fraternity (FIHF) in the translation of articles for the portal, legal documents and presentations of projects for Europe and Africa. She also translates the Thoughts of Trigueirinho series.

She explains that she doesn’t speak Portuguese, nor is very familiar with the grammar and many everyday words, although she is learning very quickly. “Do you know how difficult it is to find the translation into English of ‘gato peralta’?”, she jokes.

For her, translation is complex and surrounded with feelings: “Translating is not just changing a text from one language to another. Especially in the messages of the Divine Messengers, words and phrases carry an energy charge, and this charge must be transferred to the other language in an exact way, so as to produce the same impact. This does not mean finding a word in English that sounds the same as the one in Portuguese or Spanish. It means to find the word with the same energy charge so that the message (which in reality carries an energy charge in a specific way) can be transmitted.”

Translation and revision of the Sphere Handbook

Although she trained in translation, Fádia Maria Ramos González, of Porto Alegre, had never worked in this area, neither as a professional or a volunteer. The first task she did as a volunteer was the translation of the Sphere Handbook. In this interview, she speaks about the work, the challenges, experiences and about the professional who works in this universe.

Did you run into difficulties in translating the Sphere Handbook, a complex technical work?

I would say that, rather than difficulties, the project was a true challenge. A challenge implies a certain provocation of the subject, who feel themselves impelled to go a little beyond what they are normally able to do. And so it was with the translation of the Sphere Handbook; in this first experience of translating a technical text, they put me in charge of revising the translation of the ten translators involved in the task, following the grammar revision. There were two revisors, Mauro Rotenberg and I; we would compare the text or the original language with the proposals of ten different sources, taking care of not only the aspects related to the precision and fidelity of the original, but also harmonizing and standardizing the parts, with the goal of reaching a homogenous style. The challenge, therefore, was not limited to learning concepts and words in areas far from our life experience, such as medicine, health, administration, nutrition, the humanitarian vocabulary itself; it was necessary to build working methods, access techniques and develop procedures that would make it possible to manage the multiplicity of demands inherent to a task of the scale of the translation of the Handbook.

For you, what is the importance of this work for humanitarian responses?

The Sphere Handbook consists in a compilation of standards, guidelines, good practices and experiences of humanitarian agencies and workers from all over the world, and its objective is to guide humanitarian responses so they unfold with more quality, transparency and efficacy, especially in what is pertinent to ensuring a dignified life for refugees and displaced people all over the world. So, its availability in Portuguese makes it possible to expand the range of humanitarian servers who are able to receive the necessary information to work better in the field from the perspective of the Sphere principles and who, until then, had been unable to access the content in their mother language.With this translation, the barrier to the language is no longer there, which previously stopped the training of humanitarian agents in African countries, for example, where emergency situations get worse every day. Also, now the refugees and displaced people themselves who speak Portuguese, when they enter into direct contact with the Handbook, can count on an instrument that will offer them the chance of more consistently participating in the humanitarian response that international organizations carry out. As a result, they will be able to take on the rebuilding process of their lives and be co-responsible in the defense of their rights.

On the importance of the work of the translator:

The importance of the work of the translator resides in the capacity to disseminate knowledge, ideas and information, facilitate communication between individuals and peoples, thus drawing the human being closer to their peers. In spite of globalization, the boundaries between countries continues to be firmly demarcated by various factors, including language. In this scenario, a translation activity plays the role of eliminating those boundaries, and even move through territories that otherwise would not allow themselves to be penetrated by different customs and cultures. It is about a task that transcends linguistic boundaries, since it is not limited to the mere transposition of words from one language to another: translator and translation are elements in the service of interculturalism, intermixing different cultures and fostering a dialogue between them.

To translate is a highly complex cognitive activity that besides requiring knowledge, needs sensitivity. Commentary.

It is said that, as a highly complex cognitive activity, besides knowledge, translation requires sensitivity. This means that in the process of reading and understanding the text in its natural language and rewriting it in the target language, it is not enough to master the languages involved. The translator must use other abilities and resources that predispose them to recognize the underlying aspect of the text – such as the function for which it is being done that must be kept in the translation – and others of an extralinguistic character, such as the recipient of the final product, who must not be affected by the difficulties added to the reading because of an incorrect translation. But it is on a more inner level where the sensitivity of the translator is challenged during the whole development of a translation. They must pay attention to their own interaction with the text and the universe it holds, the mental as well as emotional mechanisms that take place within them. They must be an observer of themselves, of how they use the experiences and knowledge that are activated from the first contact with the material and influence them in the act of translation. They must be willing to reformulate initial hypotheses, going constantly back and forth over their own steps and decisions until finding the solution for the most adequate translation. For this, a certain flexibility is needed. They must give up preferred words, which are not always the most efficient; have the courage to move into unknown concepts without fearing to use expressions that until then were not part of their vocabulary. They must be sensitive to the subtleties of the language, know how to distinguish semantic nuances and get rid of linguistic prejudices they didn’t know they had. The translator must always be open to the new, and with humility, know how to recognize when they need help, especially when they face specialized contexts they do not work with (which they are not used to or know). They must be patient, meticulous and persistent in finding the best option, although they may be feeling inevitably pressured by deadlines. Aware that the translation is a creative activity, and therefore subjective, they must still strive to reduce the subjective weight as much as possible and produce a text that expresses the voice of the original author.